My Job Interview with Jimmy Buffett

Back in late summer of ’99, I faced the prospect of what I reckon a great many people—including myself—would consider a dream assignment, getting paid to document the adventures of Jimmy Buffett. By some strange alignment of king tide moon and the Pleiades, I was on the verge of interviewing for a job to spend an indeterminate amount of time surfing, flying, touring and adventuring with Jimmy Buffett—and documenting it on margaritaville.com and who knew where else.

It was the most unusual job interview I’ve ever had. After pulling into Jimmy’s Sag Harbor driveway in my VW camper, I went to work helping him edit home videos shot in the Bahamas with his son Cameron, then we went surfing at Ditch Plains out of the then not-so-tony Montauk, New York. This was the interview process to get a job with Jimmy Buffett! It was while we were surfing Jimmy asked me, “Have you ever been to Key West?”

I feared this might be the question that sank my prospects, but I responded honestly: “I never have. But ever since I read To Have and Have Not back in high school, it’s been on my bucket list.”

Jimmy’s grin and nod indicated my answer was satisfactory. “It’s changed a lot since Harry Morgan’s time,” he said. “But if you want to understand one of the places that figures pretty damn prominently in my life—and know what you’re getting into with this new job. Key West should probably be your first homework assignment.”

A couple of agonizing weeks later, a call came in from Jimmy’s right hand man, Mike Ramos. “Hey man,” he said. “Good news. Jimmy’d like for you to go to Key West”. There, Ramos said, I was to meet a young dude named Robin Smith-Martin. Rob apparently worked on occasional projects for Jimmy, including a recent video called Parrotheads in Paradise. He also ran charters and was the son of Jimmy’s longtime business partner—a lady named Sunshine Smith. As Mike told it, Rob was a solid cat. He would show me around, introduce me to some of the crew at Margaritaville and sort of help me get my bearings.

Jimmy had a business partner named Sunshine? I thought that was pretty cool.

On a late summer’s day I boarded a puddle jumper from Miami to Key West. I’d flown above the Keys to the Caribbean a good many times at this point in my life, but always at 30,000 feet. Flying fairly low along above US 1, I marveled at the different hues and infinite shades of blue where sand, reef and abyssal depths mingled. I had no idea there were so many other small islands both inhabited and uninhabited in the Keys chain. How many times, I wondered, had Jimmy made this flight at this point in his life. If things went well, I wondered how many more times I’d make it. Soon the Seven Mile Bridge appeared. My best view previously had been in the film True Lies. But now there it was a couple thousand feet down, in all its glory. Jimmy made his first crossing of this bridge in a friend’s VW camper. One day about six years from now, I’d be driving down that very same bridge, listening to Jimmy spin yarns from the driver’s seat of a custom VW camper he would have me design for him–a future happening my fertile brain could yet imagine flying over the water for my first trip to Key West.

Rob pulled up to the airport in a salt-worn Jeep Cherokee. We forged an immediate bond from his first “How’s it goin’ man?”, which was spoken in a curiously South Carolinian drawl. Turns out his mom was born in Aiken, South Carolina and grew up in Columbia. My dad was from nearby Sumter, and I’d spent my summers with dad’s parents in an old saltbox cottage in Surfside Beach. Considering Rob’s easy demeanor, I wasn’t surprised to learn that he had been born in Montego Bay, Jamaica. My own pops had long been married to a fiery Jamaican who hailed from Kingston, and we both laughed when we discovered a shared ability to communicate in a passable patois.

Cruising from the airport to Rob’s house on Eaton Street, I reckon I was no different from the millions of first-timers to the island, particularly southerners who I’m sure also find Key West a fascinating yet strangely familiar place. Even if I hadn’t already read many books by Hemingway and Buffett, being here felt like a homecoming—to a place I’d never been. I knew Key West was historic, but I didn’t expect it to be this historic. I expected it to be, I dunno, something like Jacksonville Beach. Instead, the island reminded me of a lot of areas of Charleston, but specifically the Spanish moss-hung neighborhoods between King and Calhoun streets and maybe Savannah, around Forsyth Park. The broad porched single level homes wouldn’t have been out of place around Tulane University in New Orleans. The lush banana, sea grape, and banyan-lined streets and free-roaming poultry felt lifted from Port Antonio, Jamaica. The flora, fauna, and architecture was much more stimulating than I imagined.

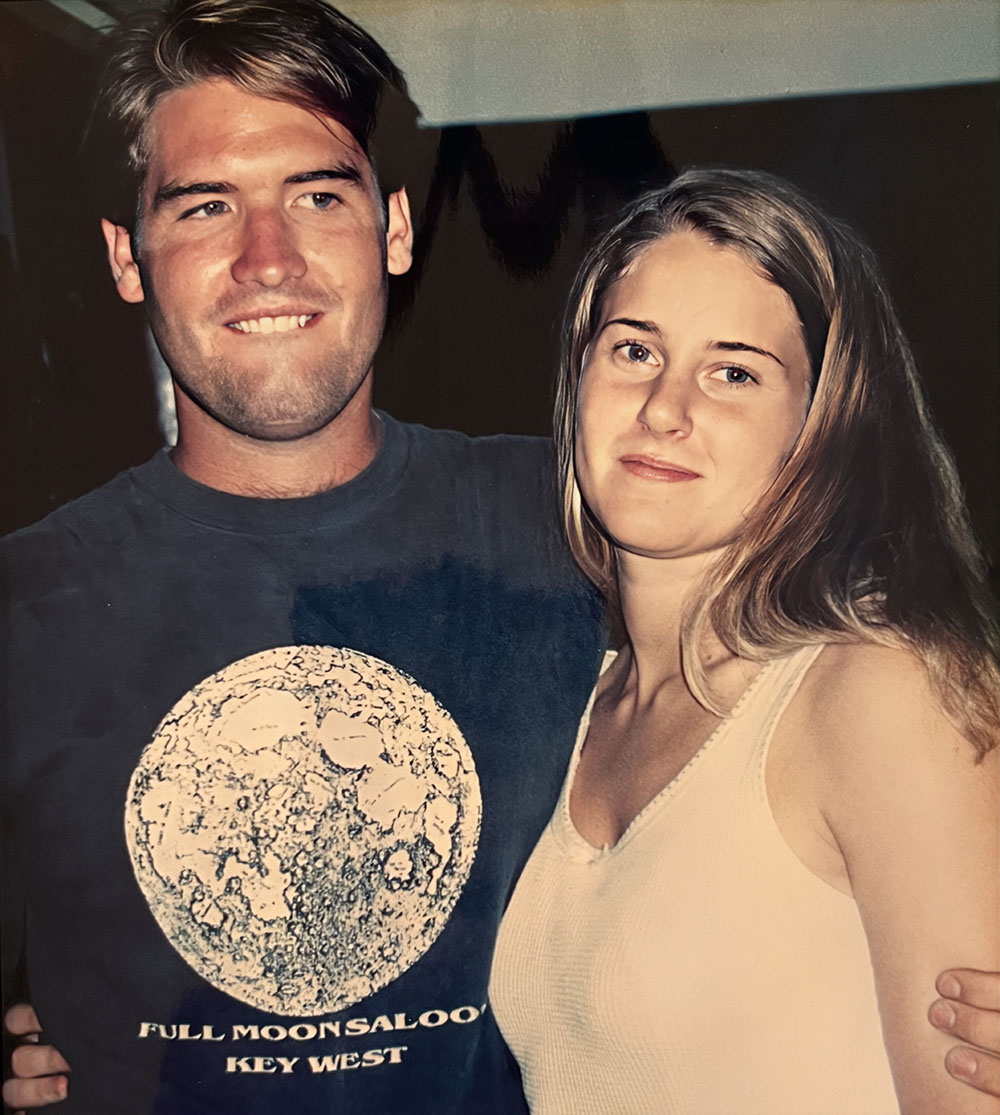

At his modest, tin-roofed home—right across from the Island City House, a circa 1880’s collection of Victorian guest houses where I was conveniently lodged–Rob introduced me to his gorgeous girlfriend (now wife). Bethany had recently moved down to the island from central New York, and was Rob’s equal in hospitality and general laid back vibe and urged Rob to take me spear fishing the next day. After our first beer, Rob started unwinding tales of growing up here as a very feral kid. His young parents—like those of his friends, focused more on enjoying the natural beauty, friendships and vices of Key West than keeping tabs on their children. It was a small island. Where were they gonna go? Coming of age heisting key limes from neighbor’s trees, roaming the streets on BMX bikes, sneaking into bars and diving and boating in Key West’s azure waters, Rob’s childhood with his brother Cayman seemed a cross between Sandy and Bud from Flipper and maybe Treasure Island’s Jim Hawkins—with a little Goonies and Scarface thrown in for good measure.

The tales of contraband I’d heard about in the Keys, from prohibition up through the era of Miami Vice and A Pirate Looks at Forty, were indeed very real. Keys-originating bales of square grouper regularly washed up on Carolina shorelines when I was a kid. Rob threw out the names of a few Charleston area shrimper smugglers and asked if I knew them, and while I did not at the time, my job with Jimmy would make those introductions some years down the road.

“My dad was in prison for running weed,” Rob said. “Jimmy was living here after he’d already gotten pretty famous. He’d come back from Aspen, and people were ripping him off—putting his song lyrics on t-shirts—making money off his fame. Jimmy wanted to sell more of his own merchandise . He’d been friends with my mom for a long time and he asked her to become his business partner.”

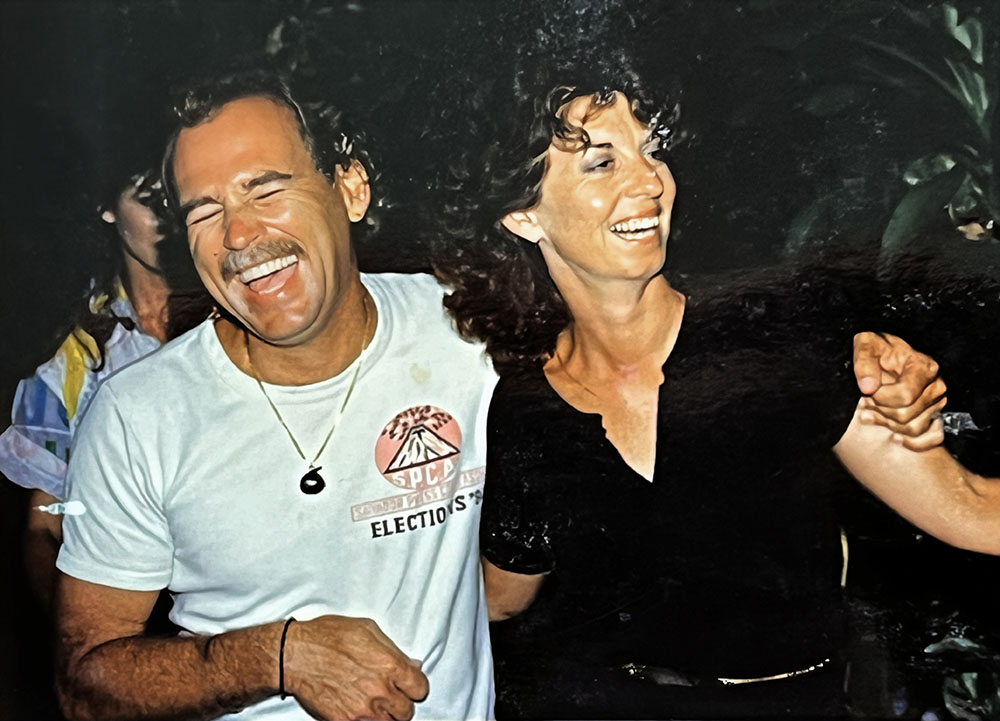

I had yet to meet Sunshine, but I had heard she was far more cosmic and down to earth than Jimmy. Yet like her famous friend, she was a born entrepreneur who, with a husband behind bars, had two sons to support. The duo launched the first Margaritaville Store in a low-slung shop in the Land’s End area of the Key West waterfront, and the business took off—both among locals and mail order fans—beyond their wildest dreams.

We biked down to Duval Street and Rob explained a little bit more about how Jimmy’s Key West operation functioned. There was the Margaritaville Cafe & Store crew here on the island, as well as a significant mail order business. They handled merchandise—books, videos, CD’s, t-shirts, and operation of the Margaritaville stores in New Orleans and Charleston. Sunshine had once handled most of Jimmy’s scheduling, business matters and new ventures—a very tall order–but that was mostly passed off now to the crew at the Palm Beach office, which included Mike Ramos and was led by a sharp Harvard MBA named John Cohlan. The tour operation was run out of Los Angeles by a California dude named Charlie Fernandez. I was fairly shocked a couple of weeks later to return home to San Clemente and discover that not only did Charlie live a half-mile from me, I recognized him from surfing at San Onofre. Radio Margaritaville was streamed out of Orlando by a veteran DJ named Steve Huntington, while the Margaritaville website was transitioning out of Key West to be run out of Houston by a guy named Coleman Sisson. Jimmy had apparently brought his computer into Sisson’s shop for a repair. The two hit it off, and Coleman still runs the site to this day. Margaritaville was a virtual office long before such a thing came into vogue.

Riding down Duval Street felt like Charleston’s King Street teleported to Barbados. There was the old Kress department store where Jimmy and Sunshine had opened the first of what would become many Margaritaville Cafes. Upstairs, above a funky, upscale variety store called Fast Buck Freddie’s were the Margaritaville offices and merchandise warehouse. The office/warehouse scene was surprisingly hectic, cramped, a bit ramshackle, and populated with smiling faces and overflowing t-shirts and CD bins. Rob introduced me to several of the crew. Amy was Margaritaville’s buyer and wife of Jimmy’s longtime roadie and fishing buddy J.L. Jamison. Cindy Thompson would be my go to for most any Jimmy related questions and requests, and Marty Lehman, aka King Coconut, was longtime editor of the Coconut Telegraph newsletter. Tall and friendly, Marty had forgotten more about Jimmy than I probably would ever know. It was, frankly, amazing to me that this small space was the buzzing hub of Jimmy’s operation. I had yet to meet the Queen Conch, Sunshine.

After meeting most of the Margaritians–as Jimmy’s Key West staff were known at the time–we rode the bikes a few blocks over to Shrimpboat Sound, Jimmy’s completely nondescript recording studio, wedged between Lazy Way and the Key West Historic Seaport. We cruised by Sloppy’s Joe’s and Captain Tony’s, then turned left onto Whitehead street where Mel Fisher’s Maritime Museum stood. Sunshine and Jimmy both knew Fisher personally. Hell, Jimmy would one day give me a photo to use in a book: Jimmy strumming his guitar and sitting alongside Mel atop a pike of gold bars—on the very day his team found the Atocha treasure galleon! I told Rob I’d once met Fisher too—around 1989, Fisher opened a little shop on Myrtle Beach’s Ocean Boulevard. I was working as a writer for a local weekly called Hot Times, and Fisher handed me a real bar of gold from the Atocha to heft. “I’d always said ‘Today’s the day.’” Fisher told me. “Then came the day.”

We pedaled on down past the Green Parrot bar and the Ernest Hemingway House. At the Southernmost Point we turned left onto South Street and down a dead end side street where we found another famous waterfront restaurant called Louie’s Backyard. Rob and his crew, including Louie’s owner Jed Tenney, had pretty much been raised here—both at the bar and on the surrounding beaches. Sunshine made Louie’s salads back in the early 70’s, working alongside Jed’s dad Phil. The regular cast of characters included Hunter S. Thompson, Jim Harrison, Tom McGuane and of course, Jimmy. So many stories and so much history crammed into a few square blocks. It was almost too much to take in.

That night, I walked solo down to The Green Parrot. Old Town Key West on a sultry night, with bicyclists rolling by–some very wobbly–bars blaring with music and conversation, tree frogs and crickets chirping—it’s just a magical place. I took a spot alongside a pair of grizzled fishermen. The angler next to me handed me a beer and said, “There’s more where this one came from!” A Yankee client had just hooked—and landed—a sizable tarpon. The tip was serious. “That sunburnt sumbitch didn’t know what the hell he was doing,” he told his buddy and me. “He was reeling when he should have let the fish run. It ’bout ripped his arms out of the sockets! His hands were bleeding.”

The next morning I rose early and wandered around until I found a guava and cheese empanada and a cafe con leche at Jose’s Cantina, a classic concrete-walled Cuban joint. Rob had promised a run on the 19-foot Wahoo he kept a few hundred yards up the street—not too far from Shrimp Boat Sound. He only paid $140 a month for the slip, he said—a hell of a deal, considering the cathedral hull could have him idling in Key West Harbor in a matter of minutes. We loaded up masks and snorkels, and Rob fired up the 150 Johnson.

Puffy clouds dotted the sky like a painting, and not a drop was out of place on the glassy water. Captain Rob throttled up and ran us north out of the bight, past Fleming Key and out across, basically, a mirror. Off the coast of the Carolinas, or anywhere in the open ocean, even if it’s glassy, there is always some swell to alter the water’s surface. In this vast protected stretch of backcountry, you couldn’t tell where the sea ended and the sky began, and all I could see as any sort of landmark was the occasional Stone crab buoy. It was disorienting—but heaven on earth.

There was no GPS, but even after we were well offshore, thanks to patches of reef and stretches of sand and seagrass clearly visible below, Rob knew exactly where we were. Eventually, he found his hidden reef and dropped anchor. We donned gear and headed over the side. I had the great fortune of growing up amongst surfboards and Hobie Cats, but the Atlantic of my childhood was perennially murky. Down here in the Keys, gliding along above the grunts, angelfish, sergeant majors, parrotfish and a couple of slow cruising stingrays, I thought maybe surfing could be a fair trade. Rob was probably ten feet below, gliding along the bottom with his speargun. We came upon a Sprinter van-sized rock that looked to have a passage beneath it. Rob dove deeper to check it out, and as he did a bigass shark–maybe 8 feet–rocketed out from underneath towards him before quickly turning away. After a moment of shock, I realized it was a (mostly) harmless nurse shark, but man, what a rapid reminder that we were definitely not at the top of the food chain.

I surfaced with my heart pounding. A few seconds later, Rob did the same. “That was pretty cool huh?” he asked laconically.

Yeah, it sure as hell was.

I had a plane to catch, so after Rob fileted a few hogfish for his dinner that night, we drank a beer and flew back across the glassy water into Calda channel and back into Key West harbor and Rob’s slip in front of the Waterfront Market. I tried to visualize this place in the past: the rum runners, the billfishers, the shrimpers, the wreck chasers and the writers—all those folks who came before me. It was, frankly, overwhelming. Even though, as Rob said, the place had changed a great deal, there was still a lot of magic here. And it was just so obvious why this pirate town would play such a big part of Jimmy’s life and songs. I’d only scratched the surface of the surface on this trip, and I didn’t even get to meet Sunshine.

The good news is . . . I got the job!

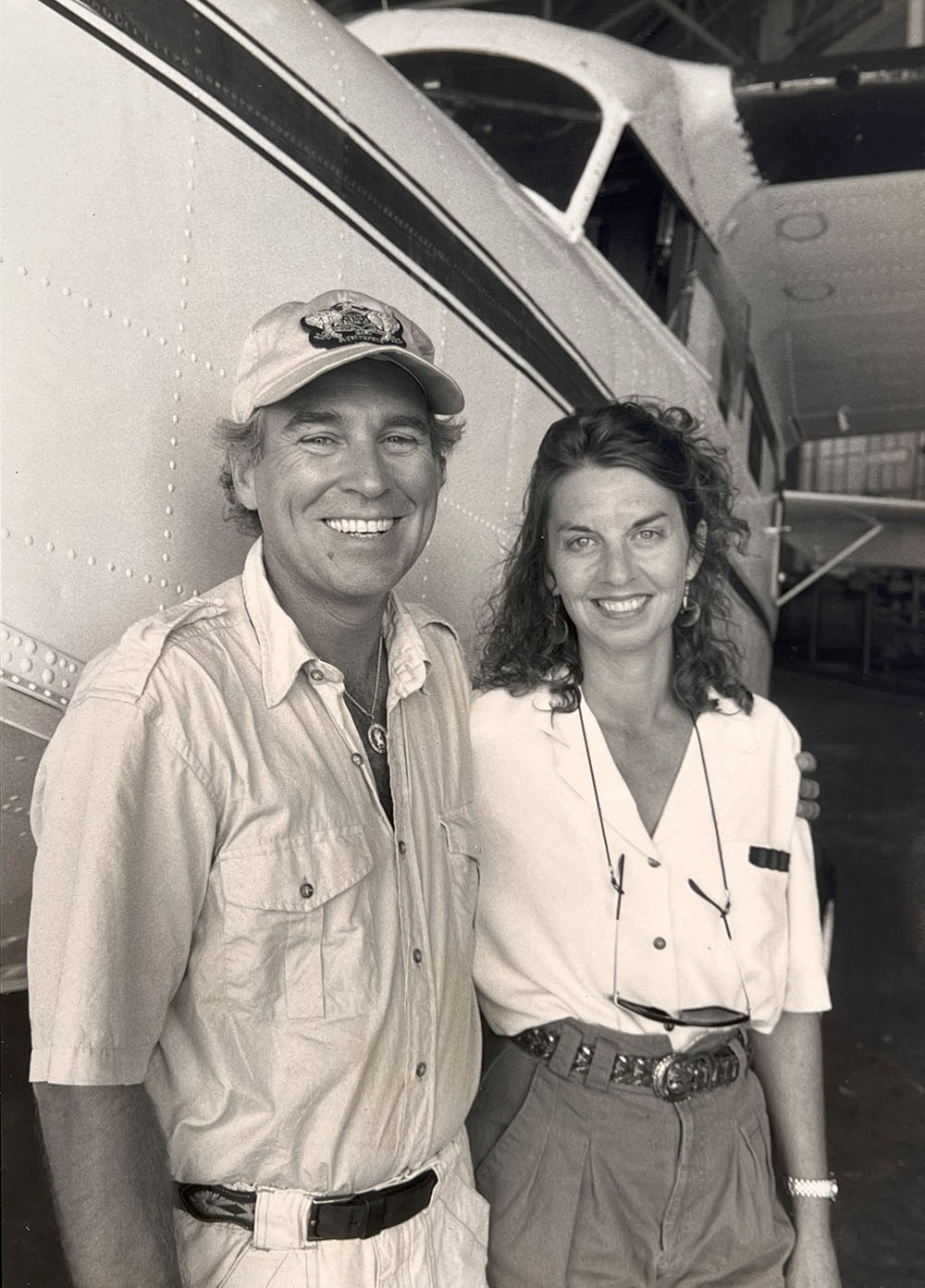

My first trip to Key West was a terrific and informative first taste of an amazing year adventuring with Jimmy Buffett. Within a month I was flying to St. Barths with Jimmy and the Cosmic Muffin herself, Sunshine Smith. The job took me surfing from L’Orient to Lahaina, flying escapades throughout the Bahamas aboard Jimmy’s Cessna float plane–I nearly fell out of the side hatch of Jimmy’s famed Albatross seaplane. We hacked agave plants at rancho tequila in Guadalajara. I hung with Jimmy and his amazing band for multiple legs of his summer tour, and I nearly drowned on several occasions scouting surf breaks for the boss mon. So many incredible tales to share about working and playing with Jimmy. I hope everyone makes an effort to tell their Jimmy stories. Let’s keep the party going!

Learn More About Chris Dixon

Purchase the Current Issue of OurKeyWest Magazine

- My Job Interview with Jimmy Buffett - September 6, 2025

Conch Town Records

Conch Town Records Tall Ships And Their Masters

Tall Ships And Their Masters Goombay Festival

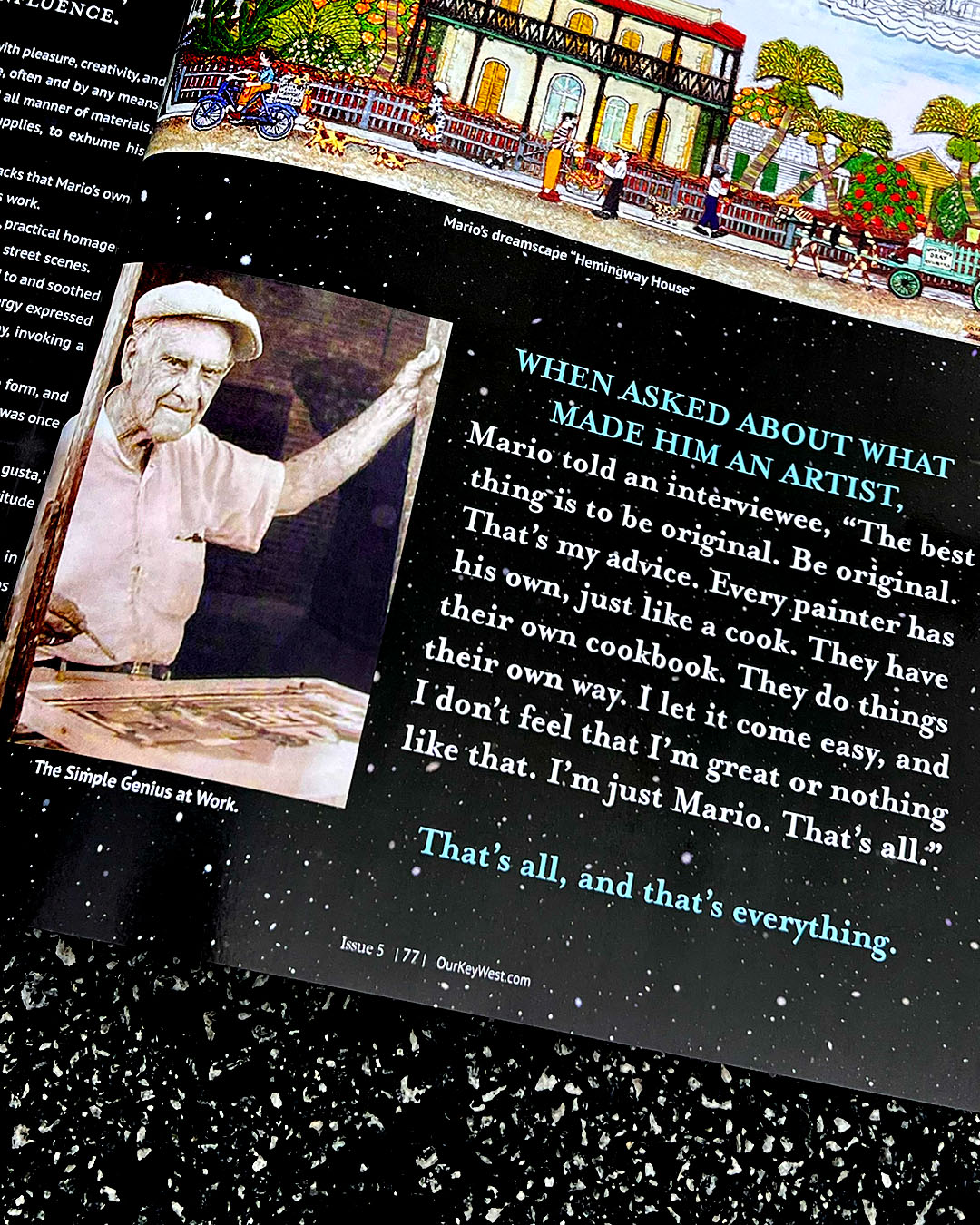

Goombay Festival Mario Sanchez – The Birth Chart

Mario Sanchez – The Birth Chart